|

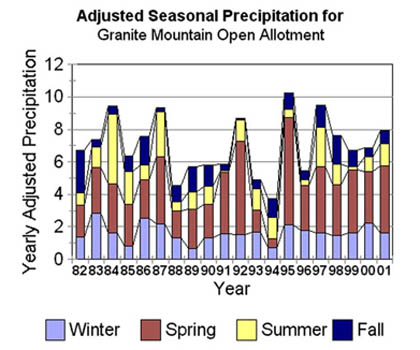

| In her book The Western Range Revisited University of Wyoming law professor Debra Donahue argues that livestock production cannot be justified on public lands receiving less than 12" of annual precipitation. Between 1982 and 2002 this region never received more than 11" per year, and the years 1999 to 2002 experienced severe drought. |

In addition to providing forage for cattle, the allotment provides habitat for large wildlife species such as antelope, elk, mule deer and wild horses. A variety of small and nongame wildlife also make their homes here including ground squirrels, cottontails, jackrabbits, badgers and coyotes.

Greater sage grouse,

a bird in decline throughout the West, in part, from impacts of

ranching, has six strutting grounds (leks) on the allotment and uses the region throughout the year.

The U.S. government, as is typical of its management, has allocated the vast majority of the allotment’s forage to livestock. According to the Granite Mt. Open Allotment #1636 Allotment Management Plan, April 20, 1999 (Draft) the allocation of forage on the allotment by Animal Unit Months (AUMs) and by percentage of total forage is as follows.

Percentage of

AUMs Total Forage

Cattle: 12,585 81.0

Wild Horses: 1,835 11.8

Antelope: 889 5.7

Deer: 227 1.5

Elk: 0

(although reportedly 75-125 elk

occupy the Beaver Rim)

I visited the allotment with the late

Ray Corning as my guide on September 20, 2001, at which time the photographs shown below were taken.

|

|

|

|

|

Ray Corning measured the water temperature here at the source of Tin Cup Creek and found it to be 46º F. A short distance downstream the temperature was 12º F. higher. Without cattle grazing here, breaking down the banks, the creek would be much narrower and deeper. Consequently, the water would remain cooler throughout its course, which is essential to survival of native fish.

Note also the bumpy terrain that parallels the stream and extends to the uplands. The bumps are known as “hummocks” and were a cause of great concern to Ray as you’ll read below. |

|

Ray Corning, in a letter of August 2001 to the Lander Journal, explained how trampling by cattle destroys wetlands. Those issues relevant to Tin Cup Creek are here excerpted from his letter.

A wetland can be viewed as a layer of plants overlying a giant sponge of humus and humic materials, mycorrhizal fungi, soil bacteria, and decomposing materials renewed by a supply of dead growth from surface plants. This layer has a high concentration of water from the spring through the fall months.

Wetlands in good health provide water throughout the growing season, even in times of drought. Sage hen chicks successfully hide in the wetland when danger is near, and the hens fatten while watching the young. Numerous other birds use the wetlands, as do wildlife and domestic cattle.

If wetlands are in poor health, they are a sorry sight. Often, little water exists, only a small portion of the wetland is moist, and no water is available for downstream use. At this point streams begin drying up. Pathways used by cattle become trenches as continuous drying and trampling erodes away centuries of humus deposition.

The next progression is to barren hummocks of dried out soil, generally painted white by saline salts left behind as moisture evaporates. Production of sedges and grasses steadily declines and is increasingly dependent upon individual precipitation events. Sage hen production also declines as chicks are exposed to predators, just as use by all other frequenters of wetlands, including cattle, dwindles. Streams may become intermittent, and effects of a drought can become catastrophic under such conditions.

|

|

|

|

|

As Ray explained, cattle paths through the wetland surrounding Tin Cup Creek have given rise to hummocks. The wetland is in a latter stage of decline as indicated by white salt deposits on once moist ground.

Tin Cup Mountain, near the western boundary of the allotment, lies in the distance.

|

|

| Mike Hudak photographing a hummock at Tin Cup Creek. Photo by Ray Corning. |

|

This is the hummock that I’m shown photographing in the previous photo. Note the quarter on top for size comparison. |

|

Tin Cup Creek a short distance from its source displays characteristics typical of cattle grazing. Rather than being deep, narrow and meandering, the creek is shallow, wide and straight. Rather than being thick with vegetation, the banks are punctured by cattle hooves and sparsely dotted with vegetation cropped closely to the ground. Erosion, facilitated by grazing of streamside vegetation and trampling the banks, leads to downcutting of the entire stream as witnessed by the high ground on the right side of the photo.

When streams such as this were still in healthy condition they supported two subspecies of cutthroat trout. Were such fish reintroduced into this stream they would perish due to high temperatures and high levels of sediment. |

|

|

I generally avoid comparing locations between allotments, especially when they reside within different geographical regions, but in this case I’ll make an exception. Carter Creek, on the

Cumberland/Uinta Allotment in southwestern Wyoming, suggests how Tin Cup Creek would eventually look if cattle were removed. This section of the creek, photographed in September 2001, has been free of cattle since 1994. The narrowness of the creek and the abundant vegetation lining its banks are indicators of greatly improved health. |

|

| Just outside the wetland region of Tin Cup Creek we come to what Ray Corning dubbed a “cattle socializing area.” No vegetation remains that would benefit wildlife. |

|

Epilogue

Drought conditions continue into 2002

On January 18, 2002, Jack Kelly, field manager of the Lander Office of BLM, issued a letter to livestock permittees in his region telling them to anticipate further restrictions on grazing in 2002. Specifically, he warned, “If drought conditions continue, no turnout, or delayed turnout coupled with an early come-off date may be necessary this coming grazing season to adequately protect and manage the public rangelands.” Mr. Kelly also reminded the permittees of the “multiple-use” mandate of the public lands: “we must keep in mind that public lands also provide forage and habitat for a wide variety of wildlife, and in some areas, wild horses. Improved livestock distribution must be balanced against the forage and habitat requirements of these other species.”

It is welcome news that BLM is finally showing more concern for wildlife, but it’s unfortunate that it has taken one of the worst droughts yet recorded in Wyoming to prompt these actions. Had reductions in cattle stocking been initiated years ago, there would not be the loss of vegetation production to the extent that occurs on the allotment today.

For more information about the allotment during 2002 please see my photo essay

Granite Mountain Open Allotment, Wyoming (2002).

|

|

|

|

These are your public lands. How well do you think those responsible for managing livestock grazing in the monument are doing at protecting the region for wildlife? Please convey your thoughts to officials at

Letters to newspapers are also an effective way to express your views to resource managers:

Riverton Ranger

P.O. Box 993

421 E Main St

Riverton, WY 82501

|

Phone: (307) 856-2244

Details of letter submission: http://dailyranger.com/

|

|

|

|

|

Text and Photos © 2004– by Mike Hudak, All Rights Reserved

|

|